The battle of broken knee

By Tim Engstrom

BOVEY — Some battles are fought on the operating table.

Such is the story of Peter Dubey, a Legionnaire leading a post way up in God’s Country, where the lakes are abundant and the woods are all-around.

He is the commander of Lawrence Lake Post 476. It’s a rural post — rural as in not in a city — to the northeast of Grand Rapids. It’s in Lawrence Township, and there is a scenic body of water called Lawrence Lake.

Dubey, 39, graduated from Appleton East High School in 2001. If you visit his country home, you find he’s a major Green Bay Packers fan.

He joined the Wisconsin National Guard in 2000 because he had a longtime interest in the military. His mother is from Poland, and, as a boy, he often heard of the freedoms they didn’t enjoy under communist rule.

His father, an American linguist fluent in Slavic languages, met her in the 1980s when he stopped at an apple orchard while working for the federal government on American-Polish relations. When he was able to stop in, he would leave contraband, such as vinyl records. They wed, and she came to Wisconsin.

Dubey’s basic training was the summer before his senior year of high school. The summer after his senior year, he went to training to become a mortarman. He drilled in Appleton with the 32nd Infantry “Broken Arrow” Division’s HQ Company.

In 2006, Dubey wanted to go into radiology, and he signed on to the Army Reserve’s Medical Corps. However, after three months, word came: “We have too many.”

He opted to go active duty instead. But at MEPS in Milwaukee, he found out the Army didn’t need radiologists, either, but it did need intel.

“My concern was I wanted something I could use when I got out,” Dubey said.

He became a 96B, military intelligence analyst. That could translate to future work for a three-letter acronym agency: CIA, NSA, DEA, FBI, etc.

About eight months before going to MEPS, Dubey met his wife-to-be: Kailey Simon. His buddy was dating her best friend.

“He was my best friend, so we hung out all the time,” Dubey said.

Intel also appealed because, back in 1984, his father had joined the Army. He was headed to intel, too. MEPS in Milwaukee sent him to Pittsburgh, and there he found he couldn’t get in because he was married to a Pole. Poland was on the other side in the Cold War.

Dubey went to intel school at Fort Huachuca, Ariz., then the Army assigned him to be stationed at Fort Shafter, Hawaii. Kailey drove his vehicle to Fort Huachuca, and they together drove it to San Diego, where it would be shipped to Hawaii.

There, space was tight. They discovered his rank, which was E-5 sergeant, and lower could not live outside the barracks — unless he was married.

They got married on Magic Island in Honolulu on Oct. 21, 2007. They ended up in 500 square feet of housing at Hickam Air Force Base. It was a duplex with a Jack and Jill bathroom and a great view of Pearl Harbor from the backyard.

Dubey worked at U.S. Army Pacific G-2 and did a lot of information engagement with allied militaries from around the Pacific Ocean: Japan, Thailand, South Korea, Singapore, the Philippines and others.

He got to travel to Japan, Korea and the Philippines, too, and he collected many challenge coins along the way. For an E-5 to spend a good deal of time at a major command was good for his career. In 2008, Dubey applied to be a defense attaché.

Attachés serve at embassies around the globe as part of the Defense Intelligence Agency. It’s an elite role. They even enjoy diplomatic status and immunity.

He went through the lengthy application, and DIA selected him. However, the Army Military Intelligence Corps would not allow him to go because he had no deployment on his record.

Dubey tried to go to Joint Special Operations Task Force Philippines (JSOTF-P), where there was an intelligence unit providing intel to fight terrorism on Mindanao.

The G-2 colonel at Fort Shafter said no.

“I was one of two people in the G-2 shop whom he trusted to do the job,” he said.

Meanwhile, Gracie, their daughter, was born on Oct. 23, 2009, at Tripler Army Medical Center in Hawaii. It’s that famous coral pink Art Deco hospital.

He re-enlisted in late 2010 and was assigned to the 3rd Expeditionary Sustainment Command at Fort Knox, Ky. It was a logistical unit.

During his final month in Hawaii, he was diagnosed with runner’s knee, a dull pain around the knee. At Fort Knox, the docs put him on profile — no running for a month.

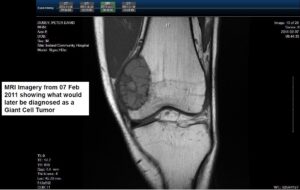

Then another. Then another. After 90 days, he asked for an MRI.

Back at Knox, the MRI revealed a giant cell tumor of the left distal femur. Doctors scheduled a biopsy and a surgery. They used two screws to set a cadaver bone in his knee. However, a miscommunication between the doctor and the therapist resulted in him being in a locked brace for 30 days — not good for his therapy. The two screws began backing out.

They opened his knee up again and inserted four screws and what Dubey called a “Cheerio plate” to secure the cadaver bone.

“It looks like a chain of Cheerios,” he said.

In March 2011, Dubey found out the 3rd ESC would deploy in April 2012 to the Middle East. He had a year to rehab to get himself is proper shape to deploy. In March 2012, he cleared that hurdle.

When he left, Kailey was pregnant. The couple didn’t know the baby’s gender yet either. The 3rd was stationed in Kandahar, Afghanistan, for three weeks, then to an undisclosed location outside Afghanistan. Dubey was promoted to E-6 while deployed.

The mission was to provide intel for the drawdown of troops and removal of equipment, such as MRAPs and Humvees. Complicating matters was, for a time, Pakistan shut down the two main southern entries to Afghanistan.

Unfortunately, Dubey began experiencing more and more pain. His doctor flew from Afghanistan and decided to have Dubey medevac to Fort Knox. Three days after Dubey arrived, Kailey gave birth to a girl they named Karlie. It was Sept. 5, 2012.

In November 2012, doctors found a big hole where the cadaver bone had been.

The doctor thought perhaps his body had rejected it, which would be not normal. In December, he had what was to be reconstructive surgery, but they found a tumor. They took out the hardware and sewed him up.

“The doctors didn’t know what to do. They were going to reassess after the surgery,” he said.

The case was sent to a specialist in bone tumors. Dr. Shawn Price of the Norton Cancer Institute went over his file and found not all the tumor had been removed.

He recommended Denosumab, a monoclonal antibody therapy that strengthens the bones and halts the breakdown of bone cells. Dubey said it calcifies bone tumors. At the time, it was a trial medicine, so he needed the green light from the Army to take it.

Dubey went to Walter Reed National Military Medical Center to see an orthopedic oncologist, who agreed with Price’s decision.

Then it was back to Fort Knox, where Dubey received one injection every 28 days for six months. He had surgery again in September 2013 with a synthetic bone and a plate with seven screws.

After, they did a CT scan of his chest to check if anything metastasized to his lungs, even though the tumor was considered noncancerous. They found a small nodule.

Doctors monitored it for a year, and they found it grew. They performed a biopsy to remove it from his right lung.

In 2014, the Army had moved him to a transition battalion. In February 2015, Dubey experienced pain in his leg again. Doctors removed the hardware and found the bone calcified. In his profile, they determined he needed to be near an orthopedic oncologist, but the Army decided he would go to Fort Polk, La., or Fort Drum, N.Y., and neither location offered an orthopedic oncologist within a four-hour drive. He chose Fort Polk for the warmer climate.

After 30 days at Polk, he was sent to Brooke Army Medical Center at Fort Sam Houston, Texas, for a follow-up appointment with an orthopedic oncologist.

A PET scan found a giant cell tumor again had returned to his left knee. It also found additional nodules in his left lung.

Dubey got to experience a biopsy on his lung while he was partially awake, and, during the procedure, his lung collapsed. They found the nodules were not tumors.

He also was awake for a biopsy on his leg.

“They used Lidocaine, and they drilled into my bone. That was fun,” he said.

By fun, he means, not fun.

“While at Walter Reed in 2013, to get approval for the clinical trial, the doc said if it returns a third time they would amputate,” Dubey said.

Fortunately, new technology was out, and it was going to prevent any need for amputation.

On June 22, 2016, at Brooke Army Medical Center at Fort Sam Houston, the doctors cut out all bones from the bottom of his femur to the top of his tibia and fibula and installed an endoprosthesis — like a prosthetic knee attached to his bones.

From there, he did physical therapy at the Center for the Intrepid at Fort Sam Houston. It’s a 65,000-square-foot, $50 million rehab center for disabled servicemembers built entirely through private donations. Things were looking up.

“I was reaching for my water bottle, and I heard my leg snap. I even tried to walk it off, but my physical therapist wouldn’t let me walk to the hospital. Instead, they put me on crutches,” Dubey said.

He had snapped the femur where the prosthetic and bone met. Doctors put him in a wheelchair and decided to let the bone heal as the fracture did not proceed far enough up to the anchor or the prosthetic.

The stabbing pains continued, and, three weeks later, an X-ray revealed a pin had come loose.

The next day, he was allowed to return to Fort Polk for four days to clear for changing his duty station to Fort Sam Houston.

“We had four days to have the movers come and pack and clear the post. Being in a wheelchair in a two-story home was not the most ideal situation on top of the stress of trying to clear the installation,” Dubey said. “That put a lot of work on my wife.”

During the move, he ended up with a staph infection from the removal of the bad pin.

Surgery again. This time, they replaced the entire endoprosthesis in his femur and gave him seven weeks of antibiotics. He was on 150 mg of prescribed Oxycontin a day and had been on some type of opiate to manage pain for the last six years.

Three months after surgery, Dubey started reducing 10 mg a week and felt the withdrawal impacts for three to four days each time.

“Opiates are powerful, but I only was dependent on them when I was prescribed,” he said.

While at physical therapy using an anti-gravity treadmill, the hardware in his knee broke where it was attached to his femur, so now the dosage went back up.

Doctors operated again in March 2017. They extended the prosthesis halfway up his femur into bone not previously touched by metal. It was the 10th and final surgery.

Thirty days later, he read about ketamine’s effect on resetting opiate receptors. Each time cells in the body get an opioid, receptors get plugged, so they make new receptors, and it is why patients continually need an increased dosage.

“I had lived in constant fear of being in pain,” Dubey said.

At Brooke, he received a ketamine infusion, and he went through five days of treatments and mild hallucinations in the ICU.

During this, Brig. Gen. Jeffrey Johnson, commander of the hospital, and his wife, Paula, visited him and mentioned bringing the Army chief of staff by the next day.

“I had no idea whether I imagined this or not, and I texted my wife to ask Paula if it was real,” Dubey said.

Kailey and Paula knew each other through the Warrior Family Support Center, a Warrior Transition Battalion support facility.

Dubey and his family indeed met Gen. Mark Milley. He still has his challenge coin. Milley is now the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff.

Dubey came out of the ketamine treatment on zero opiates and in less pain.

After six months of rehab, he felt he couldn’t be the leader he wanted to be. He couldn’t move like he once could. He couldn’t even kneel.

“How am I going to ask my soldiers to do something I physically can’t do?” Dubey asked.

He decided to pursue a medical discharge, and he left the Army in July 2018, with a 100 percent VA disability rating. During his final year of service, he did an internship with the DEA administration.

“That was really cool. I got to see how they did all their stuff,” he said.

Dubey applied to be an intel analyst for the DEA, but he couldn’t get a timeline for hiring or training. His family had decisions to make and couldn’t wait on the agency’s drawn-out hiring process. He and his family were participating in Operation Homefront, a nonprofit that helps servicemembers become financially independent after the military. The organization put the Dubeys in an apartment and paid the utilities, too, while they figured out their next steps.

The program allows a family to stay for 12 months or until the disability rating is determined.

Kailey’s father lived in Hibbing, and she scouted the homes in the area. They wanted a place with land. She found a nice one north of Bovey, and in December 2018, they went from the warmth of the San Antonio area to the cold of the Grand Rapids area in northern Minnesota.

One day, Dubey was speaking with an HVAC guy who invited him to attend an American Legion meeting of Lawrence Lake Post 476. He joined the Legion and the post’s honor guard, too. Three months later, they held elections, and he became the commander. He wanted to help change the public’s image of the organization.

“When I think the Legion or the VFW, I think of old guys in a bar drinking and smoking cigarettes,” he said. “I want our Legion to be family-oriented. I think it will help younger veterans get more involved.”

It was March 2020, right at the start of the pandemic. He would face a challenge.

The post did not have its own building and met at the local bar, which previously had been owned by the post.

Post 476 now has an agreement in place to join forces with a local snowmobile club, which also has many members of the post and its SAL squadron. The club is building a place along the Don Rudolph Medal of Honor Byway, across from a local gas station. Post 476 will pay to lease space.

“We will have a place to meet, a place where we feel comfortable,” he said. “I hope we can host more family functions and community engagement activities at this new building.”

Dubey loves helping people and enjoys his role in the honor guard. Lawrence Lake Post 476 is active in many ways, such as the essay contest, scholarships, fishing contests, a big buck contest, Memorial Day ceremonies, Bovey Farmers Day and running a beer garden at the county fair.

He plans to further his involvement and seek a role as vice commander in the 8th District.