Legislators question whether servicemembers can refuse to deploy

By Tim Engstrom

ST. PAUL — The Veterans Restorative Justice Act is farther than it ever has been in prior sessions. The act’s revised language made it into an omnibus bill, and that omnibus bill was approved in a conference committee May 17.

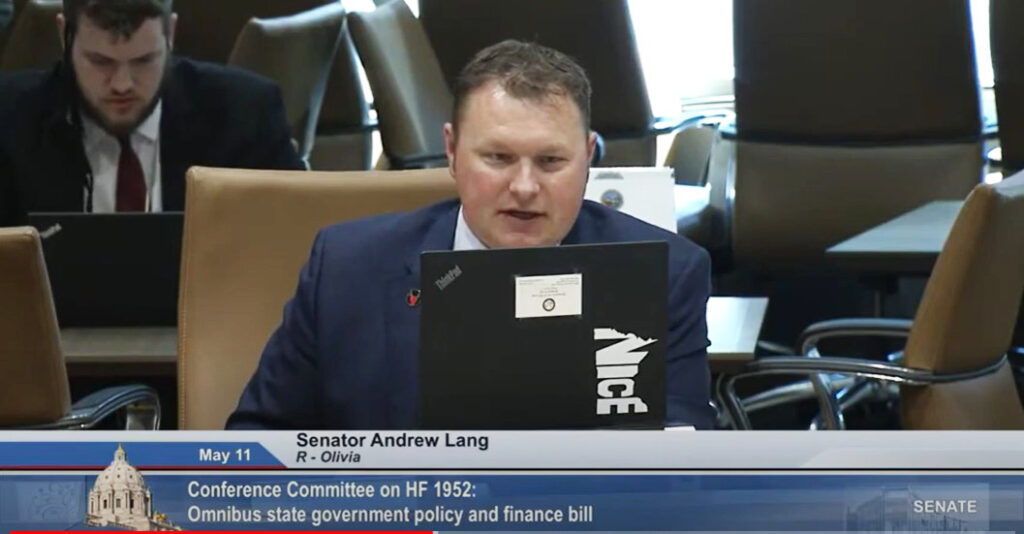

“I think, at the end of the day, we’re going to have a bill that looks pretty good and hopefully can help some of our vets out with some of the problems they encounter as they come back to the States,” said Sen. Andrew Lang of Olivia on May 14, during conference committee discussion.

But the bill didn’t pass the House and Senate because the 2021 session ended.

It is hoped that, in the special session coming on or near June 14, the bill will pass both chambers and be sent to Gov. Tim Walz, who has said he would sign it.

The political parties are close on VRJA, but other issues that divide them could stand in the way of the VRJA in June.

Standing in front of Twin Cities reporters and cameras on May 21 at the Minneapolis VA Medical Center, Walz mentioned the Veterans Restorative Justice Act publicly for the first time. He commented it would be another tool to help reduce veteran homelessness.

Lang is a Legion member with Olivia Post 186. Walz is a member of Mankato Post 11.

Asking for trauma?

Progress on the Veterans Restorative Justice Act was nearly overshadowed by a line of questioning on May 11 that puzzled veterans from several organizations.

The bill’s advocates were watching a live video feed of a conference committee to review the VRJA portion of the Omnibus State Government Policy and Finance Bill.

The line of questions — however delicately worded — implied servicemembers were asking for trauma some get as a result of combat deployments because they volunteer.

Members of the Minnesota Commanders’ Task Force, of which The American Legion is a member, were meeting over Zoom at the same time as the omnibus bill’s hearing that day. Many CTF commanders and other participants were questioning the questions.

“When the military calls on you to go, if you say no, there are legal consequences that stay with you for life,” said Minnesota American Legion Commander Mark Dvorak.

“I could never have imagined this being debated as part of this bill,” said Todd Kemery, chairman of the CTF and Minnesota president of the Paralyzed Veterans of America. “Are they saying military men and women are asking for trauma?”

Sen. Mary Kiffmeyer of Big Lake chaired the hearing. About 40 minutes into the hearing, she asked Ryan Else, legislative chair for the Minnesota Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers and a Legion member with Minneapolis-Richfield Post 435, “On the number of deployments, is that the choice of the soldier to have additional deployments or is the government mandating another deployment?”

Else replied, “As long as they stay in the service, they have to do what the service tells them.”

Kiffmeyer said, “It is my understanding, Mr. Else, that the soldier decides whether to do another deployment. It is their choice on how frequently to deploy. Now, it’s very heartwarming when we think of those who are willing to do more, but, just remember, that it is a choice as well as not. So my experience has been in the past that it has been a choice.”

She then asked for the opinion of Sen. Jeff Howe of Rockville, who served for 38 years, first in the Navy, then the Minnesota National Guard. He is a member of The American Legion, with Waite Park Post 428.

He said perhaps in the past there was a point where servicemembers had a choice, “but that’s not the case any longer.”

After the session, Howe told the Legionnaire he was referring to some U.N. missions, such as one to Bosnia, where deployment was an option. For U.S. missions, you have no choice. He said Kiffmeyer was referring to the Vietnam era, a time when servicemembers could volunteer for extensions or additional tours in the war-torn country.

Howe testified that today’s military has dwell time — recovery time stateside between deployments — and said when servicemembers are within dwell time, they can volunteer to go or remain home. Outside of dwell time, they must go.

He talked about his experience going on a second deployment two years after the first “whether I liked it or not.”

“If they tell you to go, you don’t have a choice,” Howe said.

(Sidenote: The Department of Defense says dwell time presently is two years for every year spent in a war zone.)

Kiffmeyer thanked Howe and said, “So at this table here we have experiences from previous times, and then we have that. I really appreciate it. But what I want to do here is though, Mr. Else, to make sure that as the public hears this, that there is a mixture. That there is a time at home. Some of them are voluntary. Some of them we need you; you have unique skills. So I want people to understand it isn’t just as the government sent you these number of times, that it’s always dictated through that.”

Debate then went back to the differences between the House and Senate versions. Else argued that the weaker Senate version misses the intent of the bill.

Sen. Jim Carlson of Eagan then asked Howe about when deployments are optional or mandatory.

Howe said, because of the bonds among soldiers, they would volunteer to go even if it weren’t mandatory. Some go because of their technical expertise. He talked about life in the theater of war.

“You can’t put this thing in one box. It’s all over the map,” Howe said.

Kiffmeyer, a member of the American Legion Auxiliary with Big Lake Unit 147, described her sister’s one-year tour and spoke with her about adjusting when she came home — making breakfast, school schedules, daily life in general.

Carlson described an encounter with a clerk at a Radio Shack who had been deployed and had been in a fight with his uncle at his father’s funeral during leave. He later got in a bar fight in Minneapolis and couldn’t take criticism. He had behaviors that changed him.

“I am not a veteran. I did not qualify to be in the services, and they did, and they did it for me, and I owe them a little bit of compassion for getting their life together,” he said.

Finally over the hump

The Senate language had curtailed the effectiveness of the VRJA, and The American Legion, along with members of the CTF and the legal community had pushed for the House version.

On May 14, the conference committee met again. (Conference committees comprise House and Senate members, and they alternate chairing the meeting.) This time, Rep. Michael Nelson of Brooklyn Park ran the meeting.

Lang had some language for the VRJA.

“I was talking to Sen. Kiffmeyer and Rep. [Sandra] Feist [of New Brighton] and Rep. [Bob] Ecklund [of International Falls] over the last few days, and I believe that is available, the language that we’ve been talking about.”

Nelson gave Lang credit for working on melding the House and Senate versions to create a new version. Feist had authored the House bill. Ecklund is the chair of the House committee that handles veterans affairs.

Lang said the new one clarifies eligibility, adds the Rule 25 chemical dependency assessment and brings in the Minnesota Department of Veterans Affairs to assist veterans in finding treatment programs if the federal VA cannot.

“As we proceeded forward, most of these sections between the House and the Senate language actually were very complimentary toward each other,” he said. “There was a lot of discussion, I think, on pretty small topics.”

***Let’s rewind the video.***

Earlier in the same hearing, Lt. Col. David Blomgren, general counsel to Minnesota National Guard, described language in the same omnibus bill that would fill gaps in the Minnesota Code of Military Justice to line it up with the federal Uniform Code of Military Justice. This includes law enforcement sharing case information with the Guard.

Howe had asked about how the MCMJ would align with VRJA. Blomgren said he was not familiar with the VRJA but said the Guard had rehabilitative tools at its disposal.

Those MCMJ gaps particularly pertain to domestic violence and sexual assault cases.

***Return to the end of Lang’s statement.***

Kiffmeyer asked about interaction of the VRJA and military code of justice.

“These soldiers, no matter what happens to them on the civil side, are still subject to the military code,” she said.

She asked Howe to address the issue.

Howe said he has concerns about a soldier going through restorative justice, getting rehabilitated successfully, and when the county attorney gives the case’s information to the Guard, “the Guard is going to boot this guy, male or female, they are going to boot that soldier. It happens every time.”

He said when soldiers fall under the Lautenberg Amendment (prohibiting servicemembers convicted of domestic violence from carrying a firearm or possessing ammunition), they are out.

“The interaction between these two is a key thing for me, and I didn’t actually think about it until we went through this article by article,” Howe said.

MDVA Legislative Director Ben Johnson the VRJA allows the judge to be aware of the concerns Howe has raised.

Nelson asked a House researcher a question.

“Under the VRJA bill, if a person gets a stay of adjudication, it is my understanding they would retain their firearm rights. Is that right?”

The researcher said a stay would not trigger revocation of firearm rights, because there is no conviction, but he said there are other means that still disqualify possessing a firearm outside of a conviction, such as the illegal use of controlled substances.

Then Lang moved for acceptance of his amendment, which strengthens the effectiveness of the VRJA.

Howe asked about the interaction between the VRJA and the Minnesota version of the UCMJ.

Nelson said it could be tweaked afterward.

Kiffmeyer said it is difficult to change it after approval. “I’m a bit uncomfortable with moving forward if we have questions with new information that came to light today.”

Lang said Howe’s concern is valid but added it isn’t about his amendment.

“The Veterans Restorative Justice has nothing to do with the UCMJ. The Veterans Restorative Justice piece has everything to do with civil law, civil practice that happens within our courts, within our state, within our counties,” Lang said.

He said Howe’s question can be answered at another time.

Howe replied, upon consideration, that an amendment to the UCMJ piece, not the VRJA piece, would better address his question.

Discussion over the process ensued. Two votes are taken, one for the amendment, one to pass it out of committee, with Lang moving.

“Motion prevails. This is in the conference committee report,” Nelson said.

What next?

And like that, the VRJA finally passes out of conference committee after being voted down in a 2019 conference committee.

In the 2020 regular session, it died in a Senate committee, and in three 2020 special sessions, it passed the Senate but not the House.

On May 14, advocates for the bill celebrated and thanked key legislators for their support.

The conference committee’s members were Sens. Kiffmeyer, Lang, Howe, Carlson and Mark Koran of North Branch and Reps. Nelson, Masin, Jau Xiong of St. Paul, Emma Greenman of Minneapolis and Jim Nash of Waconia.

Even though the omnibus bill passed May 17, all policy bills were put on hold as the Legislature punted most everything to the June special session.

If approved in June, the act would take effect Aug. 1.

A state government shutdown looms as as political parties disagree over taxes, vehicle emissions and other matters.

A state fiscal note says the VRJA saves $1.3 million the first two years and $2.3 million the next two years.

**************************************

The truth about refusing to deploy

An active-duty or Reserve servicemember refusing to deploy is punishable under the Uniform Code of Military Justice. It is considered failure to obey an order and, in some cases, absent without leave (AWOL).

There are news stories of soldiers refusing to go.

In one from 2008, a U.S. soldier did not show up to formation when his Germany-based unit was scheduled to deploy to Iraq. He was convicted of absent without leave, reduced in rank by one level, put in prison for six months and then dishonorably discharged. In his defense, he said he wasn’t a “peacenik” or anything. He said had been to Iraq once and didn’t want to see bombs, firefights or death anymore.

In a 2005 story, a soldier refused to deploy over his belief that Iraq War violates international law. He was reduced to the lowest rank and jailed for a month, as part of a plea agreement. The court hearing didn’t mention discharge, but the reporter said the man likely would receive a less-than-honorable discharge after his jailtime.

A National Guard servicemember refusing to deploy is punishable under UCMJ when it is a federal mission, such as going to the Mideast. It is punishable under the particular state’s military code of justice if it a state-mandated deployment, such as going to Minneapolis. It isn’t necessarily based on destination, either. For example, the current deployment of the Minnesota National Guard to assist with COVID vaccines in Minnesota is a federal deployment and subject to UCMJ.

Like civilian courts, each military case and the outcome is dependant on several factors.

Though rarely used, the UCMJ does say desertion during war is punishable by death.