Capitol one

By Tim Engstrom

The Minnesota Legionnaire

ST. PAUL — Bill Strusinski is a common face at the State Capitol. He’s been involved in government since graduating from Mankato State College in political science 51 years ago.

But he’s not just another lobbyist. He’s a medic who survived combat during the Vietnam War.

The 77-year-old once served state government as the deputy commissioner for the Minnesota Department of Administration for Gov. Wendell Anderson. Gov. Rudy Perpich promoted him to commissioner, and Gov. Al Quie kept him in that role.

He’s been a lobbyist since. He is the senior director of government affairs for the Libby Law Office.

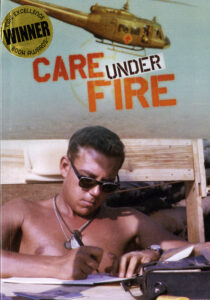

Strusinski lives with his wife, Kirsten, in Scandia, and he is a member of Forest Lake Post 225. He wrote a book chronicling his experiences in Vietnam. Calumet Editions, based in Edina, published his book in April 2020. It is called “Care Under Fire.” It is available at Amazon and Barnes & Noble.

In 1964, Strusinski graduated from Hill High School, an all-boy Catholic school in St. Paul. In 1971, a merger resulted in the co-ed school today known as Hill-Murray.

It was off to college at Mankato State College, as it was then known, and he was the first in his family to attend higher education. In October 1966, during his sophomore year, he came down with an illness that put him in the hospital. In November, he received notice that he lost his deferment, because he hadn’t met minimum requirements, and in December, he received a letter from Uncle Sam.

“Women, fun, fast cars, the library, smart professors with words of wisdom and campus parties were officially over. My youthful quest for happiness, truth and justice was about to enter a new dimension,” Strusinski wrote.

He didn’t worry too much because his father and several uncles had served.

His older brother was called to service, too, but a car crash resulting in a broken shoulder prevented entry into the Army basic training a month prior.

Strusinski was sworn in at the St. Paul Armory. Doctors certified him. Every eighth man in the group of recruits was called out. They went to the Marines.

The Army sent Strusinski to Fort Campbell, Ky. At one point during the training, an education specialist offered him job choices. Good jobs seemed to go to soldiers who enlisted, and the rest went to the drafted ones.

He had seen the TV show “Combat Medic,” and it influenced him. He already knew how to shoot, so he thought he would learn new skills. Besides, a sergeant mentioned he could put in for hospital duty in Germany or Italy, and that sounded safe.

Uncle Sam agreed to make Strusinski a combat medic, and he sent him to Fort Sam, also called Fort Sam Houston, for 10 weeks of training down in Texas.

“Finally, as we stood at attention and cooked in the hot Texas sun, our assignments were distributed,” Strusinski wrote. “The battalion commander congratulated each of us as he presented our Medic Certificates, acknowledging our competency as combat medics. Cool. But I am thinking, ‘Where are the duty station assignment orders?’”

Then the orders were passed out.

“What is Headquarters Company, 1st Battalion, 26th Infantry Regiment, 1st Infantry Division?” he asked his first sergeant.

“Son, you’ve been assigned to an infantry unit in Vietnam. You’re hereby declared to be a combat medic.”

Holy shit!

“So what about my request for a hospital assignment in Germany or Italy?”

“Son, the Army is always open to requests but never duty-bound by such trivia,” the first sergeant replied loud enough for everyone to hear. “The Army is very smart and knows best how to deploy its personnel resources.”

One last shot. Struskinski showed the first sergeant the front cover of his personnel files. On it, stamped in big, red letters was, “Not qualified for combat duty.”

The first sergeant took the files and rifled through them.

“Look here. It says you have bad eyesight and need to wear glasses. That’s the reason. But hold on, I can fix that!”

He ordered his company clerk to order three additional pairs of glasses and to make sure one was sunglasses.

Strusinski, on one hand, thought it was time to kiss his ass goodbye, but on the other, he told himself to “suck it up.”

He thought about how 1968 was a leap year. He faced 366 days in Nam, not 365.

Strusinski arrived in Vietnam on Aug. 10, 1967. After a week at jungle school, he arrived at the Big Red One’s 26th Infantry, known as the Blue Spaders.

“Shortly after my arrival, enemy rockets hit the main ammo dump where most of the base ammunition ordnance was stored. As ammo exploded, the concussions literally threw me to the ground. The smell of cordite filled the air and debris cascaded down, covering everything in a thick coat of red clay. A tall plume of fire and smoke rapidly filled the sky. It was a million-dollar fireworks display, and I had a front seat! Unfortunately, it would not be my last show,” he wrote.

The commanding officer ordered him to memorize the 1st Infantry Division’s motto, “No mission too difficult. No sacrifice too great. Duty first!”

B Company tracked down the Viet Cong who attacked the ammo dump and gave them a firefight.

The company surgeon assigned him to the men of Lima Platoon, and they were skeptical of this recruit. It wasn’t long before they were in a skirmish, and Strusinski proved his mettle under fire.

The soldiers of his platoon thought it was cool to wear their berets at night. It looked menacing and reduced the sound of branches hitting the pot. A protracted firefight changed their minds.

“On this particular night, we had neither entrenchment tools nor helmets. I hoped and prayed that no bullets would find any of us. Like all good soldiers, we learned from this patrol. Berets and soft hats were now out, and the unfashionable-but-practical steel pots were back in. More on-the-job training!”

Months later, a bullet knocked his helmet off his head.

“The steel pot was slightly altered, but my head remained intact. Lucky me!”

The book details many of his Vietnam episodes, and R&R in Japan. There are too many stories to share in one Legionnaire profile.

One story, coming on the tail of the Tet Offensive, tells of a brave and reliable M-60 gunner who covered for him while he saved the life of a flank guard who had been wounded in the open while they were on patrol near Dian, home of the Big Red One headquarters.

“Like most M-60 gunners, he was an unsung hero that day,” he wrote.

Strusinski saved the flank guard’s life, but not the man’s eye.

Not long after, the company commander field-promoted him to sergeant and made him the senior medic for the company.

It was common in Vietnam at dusk for battalions to dispatch ambush patrols, especially when the enemy was nearby in large numbers. A heavy firefight developed about 700 yards from the night defensive position. Three soldiers suffered wounds, and one of them was the medic. The remaining eight men had to fight their way back, but it would be difficult to care for the wounded at the same time.

The company medical doctor came to Strusinski and asked him, as the senior medic, what to do? He would send out a rescue team, Strusinski replied, and he volunteered to lead the rescue. He requested and the doctor granted two other medics to join him. They went with a platoon-sized force shortly after midnight and faced enemy harassment fire the whole way.

“During the chaos, I began to think about our exit strategy once we reached our destination and packed up the wounded. ‘How the hell are we going to carry these guys 700 yards on our return trip through this seemingly impossible terrain?’ This would surely be an enormous physical and mental challenge. Such an exercise was not in the Army manual or in my training background. We eventually reached our embattled brothers, who were very pleased to see us. However, I knew we were only halfway home in completing our mission. The three wounded combatants needed us to fix ’em up, pack ’em up and get ’em back to the perimeter for an enhanced level of safety and medical treatment.”

Strusinski assigned a medic to each one, and he began to treat the most seriously injured soldier. The man needed fluids and it was difficult to get an IV started. Thirty minutes later, it was time to go. Strusinski was glad he brought rigid stretchers, not canvas, for the long way back.

“I don’t know if anyone else has ever had to accomplish such a daunting task as carrying wounded comrades as far as we did that night. As we made the return trip back to the safety of the perimeter, we carried our three wounded brothers over hills, through ditches and up over downed trees.”

They made it back to the NDP around 3 a.m., but the casualty Strusinski treated died.

“This was the longest night of my life, and the entire time, I was on edge and scared shitless. It was one of the most exhausting and difficult physical and mental things I have ever done.”

The day wasn’t over. The battle continued for hours. He treated wounds, and he had medics treating soldiers who were wounded or died performing look-through-hole stupidity rather than calling-in-greater-firepower wisdom. Medics were called “docs” in the field of battle, and Strusinski cleaned the brains and skull fragments of a soldier because a fellow “doc” knew the man and didn’t want to clean up his buddy.

“In combat, you do anything to help a brother.”

Strusinski received three Bronze Stars during his tour with the Big Red One in Vietnam. He feels he didn’t do anything different than any other soldier would do. Among his decorations, he is most proud of his Combat Medical Badge.

He returned to Mankato State, where he became introverted in a sea of students with whom he had nothing in common. Dates would ask him if he had killed any babies. Such comments hurt.

One day, he noticed an ad for “Veterans Club Smoker,” and it was at the American Legion post. He met other veterans joining the organization.

“Many compatriots I met that night would become lifelong friends,” he wrote.

He regained his sanity through the Mankato State College Vets Club, which avoided the societal unrest of the day and focused on being a safe harbor for re-entry into civilian life.

His time serving his country inspired him to enter the realm of public policy, and it led to him serving his state.

He was a deputy commissioner for the Department of Administration for six years, starting in 1973. Then commissioner in 1978 to 1981, and he became a contract lobbyist in 1981.

He has experience in regulations for construction, trade, commerce, tax, finance and capital investment. His clients don’t fall on one side of the aisle or the other, but all over the map, seeking him for his abilities and experience, not politics.

“You have to gather support from both sides of the aisle and make it pass. You gather a lot of support for the policy when you do that,” he said.

Oh, and that Libby Law Firm. His wife is the boss. She is Kirsten Libby.

If you run into Strusinski at the Capitol, or at Forest Lake Post 225, ask him to tell the story of the time the company commander ordered him to treat a cow’s backside.