By Tim Engstrom

ST. PAUL — Imagine being Admiral Husband E. Kimmel, chief of the U.S. Pacific Fleet, on Dec. 7, 1941. You are standing at the window of your office, helplessly watching your fleet be destroyed.

Based in Hawaii, the four-star officer had ignored warnings from Washington about Japanese technology. He refused to do aerial recon. He disregarded intelligence. He scoffed when four Japanese carriers were radio silent. He didn’t think the Japanese would or could pull off an attack on Pearl Harbor.

A surprise attack —any surprise attack — requires two to tango: a stealthy attacker and an inattentive defender.

“We often think Pearl Harbor was a surprise. The war was not a surprise,” said Steve Twomey, author of “Countdown to Pearl Harbor: The Twelve Days to the Attack.”

Twomey spoke at the Minnesota Military and Veterans Museum’s virtual program over Zoom on Pearl Harbor Day. December 2021 was the 80th anniversary of the attack, which claimed about 2,400 military and civilian lives, destroyed nearly 20 U.S. ships and more than 300 airplanes and brought the United States into the Second World War.

Twomey (pronounced “too-me”) is a journalist who won the Pulitzer Prize for Feature Writing in 1987 for a story he did for the Philadelphia Inquirer on life aboard an aircraft carrier. A Chicago native, he and his wife live in New Jersey. They have one adult son.

“It would have been hard to have been an adult on the first weekend in December 1941 and not know the United States was about to be at war,” Twomey said.

He ran down a few among many examples:

• Walter Lippman was the most well-known newspaper columnist of the day. (He’s the guy who later coined the term “cold war.”) In his Dec. 4 piece, he wrote America was on the verge of all-out war, not with Germany, but with Japan.

• Treasury Secretary Henry Morgenthau submitted a report to President Franklin Roosevelt saying that war was imminent.

• Congressman Edwin Hall, a Republican from New York, wanted to give every serviceman $30 to take a bus or train to get home before Christmas, as a last chance to get home.

• Roosevelt wrote to Wendell Willke, his envoy to Britain and recent election opponent, that war was going to happen any day.

• U.S. merchant ships could see Japanese war ships moving in the Pacific.

The United States shifted its Pacific Fleet to Hawaii in the spring of 1940, which increased the likelihood that Pearl Harbor could be a target, Twomey said.

“The idea that the attack came out of the blue does a disservice to the information that was there,” he said.

Twomey described the Empire of Japan as bent on replacing the Western powers in the Far East. The Southwest Pacific had oil, rubber, tin and nickel, while Japan had few natural resources.

Ten days before the attack, Vice Admiral William “Bull” Halsey was at sea aboard the carrier USS Enterprise, taking fighter planes to Wake Island. He told his task force, “We have to be ready for instant war.”

On March 31, 1941, two military officers — an Army major general and a Navy rear admiral — predicted Japan would attempt to start a war with the United States without the formalities of a declaration. The report — known today at the Martin-Bellinger Report — said Japan would attack Hawaii through an air attack supported by one or more carriers that would sail by means U.S. forces couldn’t detect. The prediction said the attack would come off the coast of Oahu either at dusk or dawn.

It turned out to be dawn, with planes launching from six carriers.

“It’s exactly what happened,” Twomey said. “It was exactly what was foreseen by the Navy nine months early.”

“It’s exactly what happened,” Twomey said. “It was exactly what was foreseen by the Navy nine months early.”

The report advocated a 360-degree search of Oahu at the maximum limit of American aircraft, and if not, at least perform some measure of reconnaissance.

Why didn’t the U.S. act?

“The Japanese didn’t impress us very much. We regarded them as a strange, weird and odd people,” Twomey said. “We didn’t see them as mechanical, or original thinkers, or good flyers.”

A well-known military historian in those days, Fletcher Pratt, put forth that there were biological reasons the Japanese children don’t play with mechanical toys the way Americans do. He said the Japanese people were myopic and, thus, bad pilots, and the writer said Japanese machines, such as planes and weapons, were copies of other machines, not innovated.

The Martin-Bellinger Report didn’t carry much weight in the Navy. They didn’t think it made much sense, considering the size of the Pacific Ocean.

“Because we couldn’t, the Japanese couldn’t,” Twomey said.

That flawed thinking is called mirror imaging, where we measure an opponent’s capacity by our own, he said.

“And we couldn’t cross the Pacific,” he said.

On Nov. 3, the ambassador to Japan, Joseph Grew, sent a message to Washington saying Japanese sanity cannot be measured by American logic. He said the Japanese might make war with any country getting in its way, even at the risk of national hara-kiri.

Two weeks later, he wrote Washington about the need to guard against sudden Japanese naval actions.

Admiral Husband Kimmel, chief of the Pacific Fleet, was from Kentucky. He had graduated from the Naval Academy in 1904. He had succeeded at all jobs assigned to him, and his record was unblemished.

In February 1941, he replaced Admiral James Richardson. Ironically, Richardson was relieved, in part, because he protested moving the fleet from the West Coast to Pearl Harbor, saying it would be a logical target for an enemy.

“Kimmel was a man of offense,” Twomey said, “and he was eager to punish the Japanese.”

He didn’t want to assume a defensive posture. He figured any Japanese attack would be in the South Pacific, not Hawaii. He opposed doing long reconnaissance flights because he felt it would wear out his air crews.

America was using radio activity to track the Japanese fleet. When four aircraft carriers dropped all radio activity, it prompted Kimmel to joke, “You mean they might be coming around Diamond Head.”

He believed the carriers were simply not using their radios. In fact, they were on their way to attack his base.

Twomey said the depth of Pearl Harbor is telling to the situation and vital to understanding Admiral Kimmel.

A submarine would be spotted easily in Pearl Harbor, but an airdropped torpedo could be a threat. Pearl Harbor was 45 feet deep. Air-dropped torpedoes typically needed 75 feet of water to fall into before moving toward targets.

Washington sent Kimmel a message that the Japanese had new air-dropped torpedoes that don’t need much water depth. It plainly stated a torpedo would function in Pearl Harbor.

“But Kimmel and his staff didn’t put torpedo nets in Pearl Harbor because they felt the Japanese wouldn’t have this technology yet,” Twomey said.

While attacking Pearl Harbor was a grave mistake in war strategy, the Japanese took an enormous risk on the tactical level and even Kimmel admired how beautifully planned the attack was.

The Japanese sailed 3,000 miles to reach Pearl Harbor, and they had to refuel at sea many times. They brought seven oil tankers. They managed to avoid being spotted by civilian ships or any recon planes. Back in Tokyo, they managed to keep Ambassador Grew and others from learning the location of the fleet.

It had been assembled off Iturup, one of the remote Kuril Islands, and naval officers didn’t tell the sailors the mission until they were assembled. They thought their families would receive their medals.

“Most Japanese sailors thought it was a one-way journey,” Twomey said.

Kimmel was relieved of duty 10 days after and demoted to two stars. A commission in 1942 found him derelict of duty. Roosevelt would select Rear Admiral Chester Nimitz to command the Pacific Fleet, promoting him to four stars. Nimitz, on behalf of the United States, would sign the Japanese Instrument of Surrender four years later aboard the USS Missouri.

Kimmel died in 1968, and his family has worked to restore his rank to four stars, but no president has cleared it.

The first shot fired at Pearl Harbor was by the Americans. That naval gun, from the USS Ward, is on the grounds of the Minnesota State Capitol, just west of the Veterans Service Building.

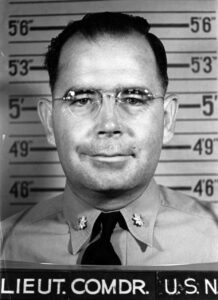

Lt. Cmdr. William Outerbridge captained the Ward, a four-stack destroyer commissioned in 1918 and built at Mare Island Naval Shipyard.

“I think he was the walking definition of a nerd,” Twomey said.

He was 35, born in Hong Kong, raised in Ohio, and was a 1927 graduate of Annapolis. He had a wife and three kids back in San Diego. He was keen to the possibility of war, and that’s why he hadn’t brought them out to live in Hawaii.

He had been the executive officer on the Cummings, and he hated the commander. He was eager to command his own ship, and on Dec. 5, 1941, he got his wish.

He wrote his wife, while his ship, the USS Ward, was on patrol Dec. 6, performing lazy figure-eights, “I hope I can have a happy and hard-working and efficient ship.” He said he could get used to being called “captain.”

The next morning, he was asleep in his quarters, and the ship was making circles. He heard, “Captain to the bridge.”

He arrived on the bridge in a kimono, ironically enough. Sailors told him there was an object in the water ahead, and it looked like the conning tower of a small submarine.

Outerbridge was a contrast to Kimmel, Twomey noted, in that he took action. He ordered the ship to general quarters and shot ahead in pursuit. It opened fire, hit the target and dropped depth charges on it.

Soon, an oil slick appeared.

He sent three messages to Pearl Harbor HQ. The first indicated the Ward had dropped depth charges. He thought perhaps HQ might think it was a false read, so the second made a stronger point, “We have attacked, fired upon and dropped depth charges.”

The third said, “Did you get that last message?”

Twomey said Outerbridge was “doing his damnedest” to tell the Pearl Harbor bureaucracy how serious the moment was, to give them one last chance to react and get the ships out of the harbor and have anti-aircraft gunners to their posts.

Few naval officers emerged beaming from the attack on Pearl Harbor, but Outerbridge did.

For quite some time, his wife received no word whether he was alive or dead. Finally, he sent a telegram that read, “Well and happy, William Outerbridge.”